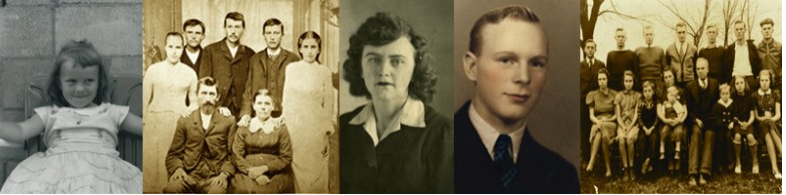

My mother

My mother grew up on the edge. It was the edge of the Appalachian Mountains, but it was in reality it was the edge of society. She was the youngest of four children in a one-parent family. Her father was a teacher in a one-room schoolhouse and her mother was convicted and sentenced for robbing trains.

As much as my mother told us what her life was growing up in poverty, I don’t think we ever fully grasped what her day-to-day tasks were like. There was no electricity and no inside plumbing in her house. She washed the family clothing down at the spring. Her brothers made a fire in the stove in the kitchen every evening before my mother cooked dinner for the family. They all ate beans and cornbread every day for dinner. My mother reportedly never owned a dress, instead dressing in her brothers’ hand-me-downs. And these hardships were before the Depression started.

But even though there was extreme poverty in many parts of the Appalachian Mountains, my mother’s family was set apart from the others in the area. They were children from a divorced family and their mother had run off with another man and was part of a mob that robbed trains. My mother and her siblings were seen as outcasts by some.

According to family story, my grandmother came back to my mother’s town when my mother was six years old. She was trying to get some of her children back to live with her and her future husband. My mother heard from her father that her mother was going to marry a “half-wit”. My mother sobbed for hours that night. When her father persisted to find out what was wrong. She admitted that she didn’t want her name changed to “Mary Half-Wit”. She told the story in a humorous way, but we could feel the pain of her childhood trying to come to grips with this situation.

My mother told us the story about going to church when she was about thirteen years old. She attended with a girlfriend, even though she didn’t have the appropriate clothing. She felt scorned because of this. At some part of the service, all the women from the church gathered around her and prayed over my mother. It may have been a religious ceremony for young teenagers in her church. But in my mother’s eyes, she was being punished for her family’s situation and for her mother’s sins. She never returned to any church except for the few times her children were in Christmas pageants and when we got married. She didn’t belong.

My mother told us the story about going to church when she was about thirteen years old. She attended with a girlfriend, even though she didn’t have the appropriate clothing. She felt scorned because of this. At some part of the service, all the women from the church gathered around her and prayed over my mother. It may have been a religious ceremony for young teenagers in her church. But in my mother’s eyes, she was being punished for her family’s situation and for her mother’s sins. She never returned to any church except for the few times her children were in Christmas pageants and when we got married. She didn’t belong.

My mother attended teacher’s college at the age of sixteen and graduated the year after World War II started. She taught for a year and hated it. She tried different careers, and eventually in 1946 moved to Lima, Ohio where her brother and sister-in-law lived.

Lil – my mother’s best friend

She didn’t try to fit in with society there. She worked in a factory and became friends with other women who were seen as “not proper”. She didn’t try to hide her differences and instead she and her friends created their own societal rules. (I later learned some amazing – even scandalous – stories about these women.) They became life-long friends, bound by their similar situations. With them she felt respected, valued and loved. When my mother was with them, she belonged and felt normal. When they were not around, she felt different from most.

They were with her when she gave birth to her first son, fathered by a railroad man who did not marry her. They were her family and part of our lives, becoming more like a grandmother to us than a family friend. Even with their support, I’m not sure my mother ever overcame this feeling of being on the outside looking in. She grew up in poverty without a mother. But with the help of her friends, she found a place to belong.

©Copyright 2016, All rights reserved. KimberlyNixon.com

Comments on this entry are closed.